This year we mostly concentrated on the year ending in "1", covering gadgets and technology from 1941, 1951, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2001 and 2011. It turns out to be a decent last digit for computers, games consoles and cars in particular. But here are some of the things that were also notable that didn't get covered.

2011 saw the launch of two rival handheld gaming platforms that were evolutions of previous devices. The Nintendo 3DS had a dual display capable of displaying glasses-free 3D on an otherwise modest hardware platform, the Sony PlayStation Vita was a more powerful device but also a more traditional gaming console. Both products competed directly against each other, but it was the Nintendo that won out although the Sony did gain a dedicated fanbase.

|

| Nintendo 3DS and Sony PlayStation Vita |

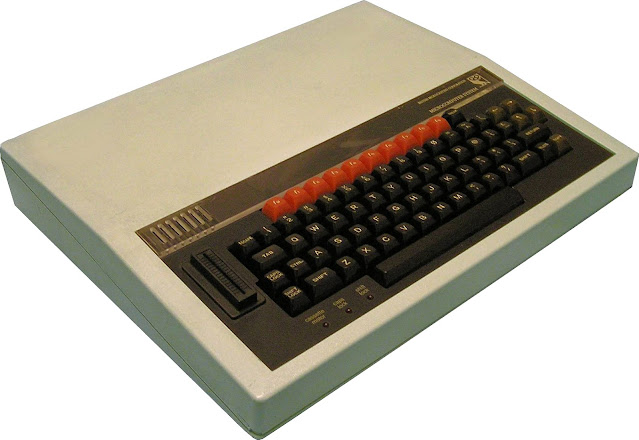

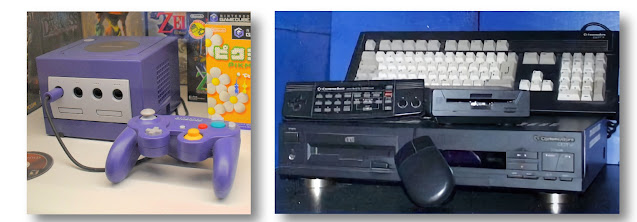

A decade earlier, in 2001, the Nintendo GameCube was launched against the Sony PlayStation 2 and the original Microsoft Xbox. In this fight, the GameCube came in third - in quite a bruising result for Nintendo.

Skipping back another decade to 1991 we see the Commodore CDTV, a repackaged Amiga that was meant to compete against the Sega Mega Drive and Nintendo SNES. It was a failure, and helped to accelerate Commodore to its demise a few years later.

|

| Nintendo GameCube and Commodore CDTV |

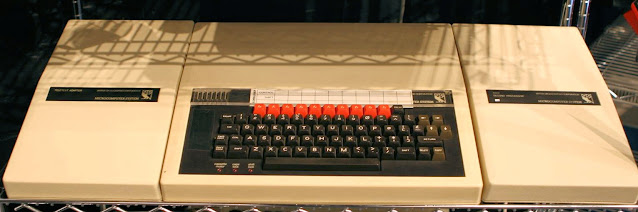

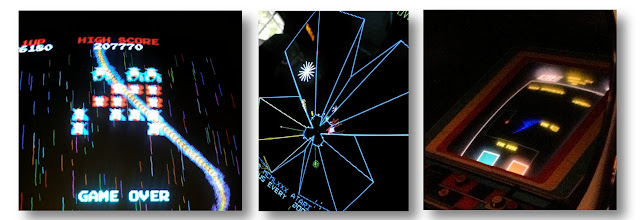

In the early eighties, the best place for video games was the local arcade and 1981 was part of the golden era of arcade machines. We've covered quite a few from this year, but Namco's Galaga and Atari's Tempest were both notable and were very different types of shoot-em-up. And if you fancied something different from endless slaughter, there was Taito's Qix which was more of a puzzle game where the player had to fill the screen with boxes while being chased by a mysterious electric entity.

|

| Galaga, Tempest and Qix |

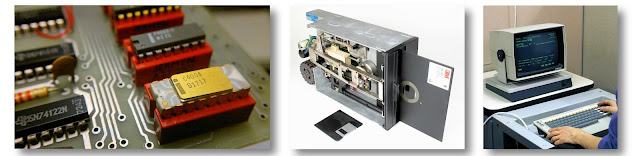

None of this would be possible without the microprocessor, and the first commercially-available device was the Intel 4004 which was launched in 1971. Originally designed for a calculator, the 4004 could be used for a variety of other purposes. A successful line of products followed for Intel, notably the x86 series of processors used in most PCs today.

The same year saw the release of the world's first floppy disks. Originally a huge 8 inches across (and very floppy), these inexpensive and transportable storage media and their 5.25 and 3.5 inch descendants were the standard way of transferring files into the 1990s and beyond.

A decade later, the Intel 8085 and a pair of 5.25" floppies could be found in the ergonomically designed Nokia MikroMikko. Nokia Data had a series of mergers and acquisitions, first with Siemens and then ICL until finally vanishing into Fujitsu.

|

| Intel 4004, 8" floppy disk (with 3.5" for comparison), Nokia MikroMikko |

Nokia have made many things over their long history, including car tyres. Today you might find Nokian winter tyres on a Nissan Patrol or Toyota Land Cruiser - both these rugged and practical 4X4s were originally launched in 1951 and were heavily inspired by the wartime-era Willys Jeep.

|

| Nissan Patrol (circa 1958) and Toyota Land Cruiser (circa 1966) |

If exploring in your Japanese offroader with your Finnish tyres, you probably want a good system to tell you where you actually were in the world. Today you'd use a GPS system, but that wasn't an option back in 1981 when Honda announced the world's first in-car navigation system, the Electro Gyro-Cator. Instead of using satellites, it used inertial navigation and a set of transparent maps fitted over a screen. It was bulky, expensive and of limited use, but eventually the first in-car GPS system was launched in 1990 by Mazda.

|

| Honda Electro Gyro-Cator |

Stretching things out a bit more… if you found yourself off-roading in your big Japanese 4X4 with Finnish tyres in the 1970s or 1980s and you wanted to make a high-quality video recording of your journeys, the choice of professionals was a Sony U-matic recording system which was launched in 1971. Capable of capturing broadcast-quality images, the U-matic was the choice of professionals. Smaller than a traditional film camera, most units were still quite bulky and required a crew of two or three - one for the camera, one for the recorder unit and perhaps one for the microphone boom. Perhaps on your exploration into the wilderness you might want to pack some supplies, and there's a good chance that these might include Heinz Baked Beans, a staple of tinned food since 1901. Luckily the Japanese make some of the best can openers in the world too..

|

| Sony U-matic in a carry bag and Heinz Baked Beans |

Image credits:

Nintendo 3DS: Evan-Amos via Wikimedia Commons - CC0

PlayStation Vita: Evan-Amos via Wikimedia Commons - CC0

Nintedo GameCube: BugWarp via Wikimedia Commons - CC BY-SA 4.0

Commodore CDTV: Patric Klöter via Wikimedia Commons - CC BY-SA 3.0

Tempest: Russell Davies via Flickr - CC BY-NC 2.0

Galaga: David via Flickr - CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Qix: Joho345 via Wikimedia Commons - CC BY-SA 3.0

Intel 4004: Simon Claessen via Flickr - CC BY-SA 2.0

8" floppy disk: Michael Holley via Wikimedia Commons - CC0

Nokia Data MikroMikko: Nokia

Nissan Patrol (1958): Sicnag via Flickr - CC BY 2.0

Toyota Land Cruiser (1966): Sicnag via Flickr - CC BY 2.0

Electro Gyrocator: Honda

Sony U-matic: Joybot via Flickr - CC BY-SA 2.0

Heinz Baked Beans: Ian Kennedy via Flickr - CC BY-NC 2.0