The video terminal is the unsung hero of the computing world. Often toiling aware in warehouse, factories, colleges, shops and other places out of the public eye, the video terminal was a dependable workhorse for decades… well into the era of the PC.

Arguably the king of the terminal market was Digital Equipment Corporation (“DEC” or just “Digital”) who made terminals that were attached to minicomputers or mainframes, where they could run a wide variety of centralised applications that typically ran on Unix or VMS boxes.

They comprised of not much more than a display, keyboard and serial interface – and although they were not always cheap to buy, they were certainly cheap to run with no moving parts and complete immunity to computer viruses and other malfeasance. You could plug one in and forget about it for years, and it would keep doing its job.

|

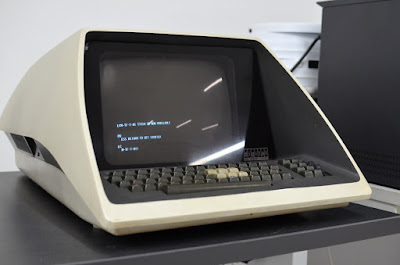

| DEC VT05 |

It could only display uppercase characters, but the keyboard could enter both upper and lowercase. Quite how you were meant to tell what you were typing is a mystery. Maximum data transfer rate was 2400 baud. The VT05 had a video input so you could display other things on the monitor, and mix them together with the text. The VT05 was around for five years until the much more capable – and conventional – VT52 was launched.

|

| DEC VT420 |

The VT420 also supported dual sessions, typically by using the two serial ports on the back. Not only could you interact with two utterly different systems, but you could also copy-and-paste between them. That might not seem like a big deal now, but back in 1990 most people still couldn’t paste data between applications on their PCs so it was kind of a big deal.

The data transfer rate was a speedy 38,400 baud using the compact phone-like MMJ sockets, the screen had a maximum capacity of 132 x 48 lines of text and the latest revision of DEC’s legendary keyboard – the LK401 – was almost perfect in every way except for the annoying lack of an Escape key.

Where the VT05 marked a point near the beginning of DEC’s journey, the VT420 marked a point near the end. The days of centralised minicomputers were starting to fade and throughout the 1990s PCs and Macs became more capable professional computing environments. The VT420 was a success but it lasted just three years before being replaced by the VT520 which was almost identical. DEC sold the entire terminal division in 1995 and they themselves were taken over by Compaq in 1998, who were then taken over by HP in 2002.

The VT range soldiered on with Boundless Technologies until 2003, and other manufacturers either closed down or shuttered production in the following years, including Wyse and Qume until there were none left.

Even though the manufacturing of terminals dried up, the computer systems that relied on them still exist. VT terminals are still in use around the world, but newer installations will typically rely on a PC with some terminal emulation software – a more complex and less reliable solution.

Today a DEC VT420 in good condition second-hand can cost a couple of hundred pounds, and maybe budget a thousand or so if you want to acquire a VT05. Of course terminal emulators can be had for less, a client such as PuTTY is free or Reflection is a more commercial offering.

Image credits:

Matthew Ratzloff via Flickr – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Adamantios via Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 3.0