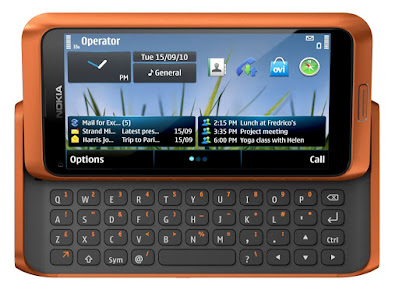

Introduced September 2010

Looking back at Nokia, there was a point in its history where it slipped from being the market leader to a market failure. The Nokia E7 sits on the cusp on that change.

|

| Nokia E7 |

The Nokia E7 was the spiritual successor to Nokia’s long-running range of Communicator devices. Big and often bricklike, the Communicators had bigger screens that almost any other phone combined with a large physical QWERTY keyboard. Oddly, the Communicators often lagged behind in terms of features – the Nokia 9210i lacked GPRS for example when rivals had it, and the Nokia 9500 didn’t have 3G just when it was becoming common. It wasn’t really until the E90 in 2007 when it caught up in communications terms… a bit odd given the “Communicator” name.

Anyway, more than three years had elapsed since the launch of the E90 and in that time Apple had released their third-gen iPhone and Android devices were eating into Nokia’s market share. Many Nokia fans who had bought the E90 had moved on to other smartphone platforms. Nokia needed something special, and it looked like the E7 could be it.

Sleekly designed, the most prominent feature of the E7 at first glance was the huge 4” AMOLED capacitive touchscreen display, bigger than almost anything else on the market at the time. Hidden underneath that was a large keyboard that could be found by sliding the screen. A decent 8 megapixel camera was on the back, and the E7 supported 3.5G data and WiFI. GPS was built-in along with an FM radio and 16GB of internal storage.

|

| Nokia E7 |

All of this was powered by Symbian^3, Nokia’s latest version of their S60 operating system. This supported all the usual applications plus document editors, comprehensive email support, built-in navigation and excellent multimedia capabilities. It was quite possibly the best Symbian phone that Nokia ever made. But since nobody uses Symbian today, something must have gone wrong..

Nokia had both been very early to the touchscreen smartphone party and very late at the same time. The Nokia 7710 had launched in 2004 – years before the iPhone – but the technology wasn’t quite there and consumers stayed away. Nokia’s next attempt at a mainstream touchscreen smartphones was the 5800 XpressMusic which launched waaay after the iPhone. The 5800 proved popular but it was pushing S60 almost as far as it could go.

Symbian was meant for an earlier era of handheld computing. First appearing in 1989 as Psion’s EPOC operating system (see on the Psion Series 5 for example) it was designed to run smoothly on minimal hardware. The Series 5 for example had a puny 18MHz processor and 4MB of RAM, but by the time the E7 was launched it had a 680MHz processor and 256MB of RAM… hardware which in theory could run something more sophisticated. Rival Apple and Android devices both ran on operating systems descended from Unix which allowed a much richer environment for software developers. Developing for Symbian was harder, but it was worthwhile because even in 2010 Nokia’s OS was the market leader – even if it was beginning to fade.

|

| Nokia E7 |

It wasn’t as if Nokia lacked an alternative – the 770 Internet Tablet launched in 2005 running Nokia’s own take on a Unix-like OS called Maemo. But it wasn’t a phone and development of the platform was slow, but eventually they came up with a practical if somewhat rough around the edges smartphone in the Nokia N900. It looked likely that whatever would succeed the N900 would be a winner, but instead Nokia decided to merge Maemo with the Intel-led Moblin platform… a decision which completely derailed the strategy to replace the N900.

Stuck with the limitations of Symbian and with no next-gen product on the horizon, Nokia’s future was beginning to look uncertain. Even though sales were strong, it wasn’t clear how they could compete in the long term. But as it happens just a few days before the announcement of the E7, Nokia also announced a new CEO – Stephen Elop.

Elop realised the predicament that they were in and explained it to Nokia employees in the now-infamous “burning platform” memo that was leaked to the press. Ultimately Elop wanted to move Nokia away from Symbian and Maemo/MeeGo towards Microsoft’s new Windows Phone 7 OS. This was a bold move as Microsoft’s platform was very new… and Microsoft themselves had lost market share sharply to Apple. The plan was that Symbian would eventually be discontinued, but Nokia were hoping there would be a gradual transition of customers from Symbian to Windows. But that’s not what happened.

Dubbed shortly afterwards as the “Elop Effect”, the impact on Nokia’s sales were disastrous. Elop had effectively made Symbian a dead-end platform and that killed off pretty much any market appeal to customers. Sales fell through the floor, and worse still Nokia didn’t have a product to replace it (the first Lumia handset launched late in 2011). Far from being a smooth transition from one platform from one platform to another, it simply persuaded Symbian fans to jump ship… mostly to Android.

Less than six months after the announcement of the E7, Symbian was effectively dead. A trickle of new Symbian devices emerged from Nokia with the last mainstream handset launched in October 2011 and the final ever handset being launched in February 2012. None of them sold well. But then neither did the Windows phones that followed.

The E7 marks the point when Nokia’s seemingly invincible empire crumbled. The last high-end Symbian smartphone, the last of the Communicators, the E7 might have been a game changed if it had been launched three years earlier. Today the E7 is quite collectable with prices for decent ones starting at £60 or so with prices into the low hundred for ones in really good condition.

Image credits: Nokia