Introduced April 1982

If you were a British child of the 1980s, the chances were that you possessed one of the holy trinity of the BBC Micro, Commodore 64 or the Sinclair ZX Spectrum. A rivalry leading to many playground arguments, these three machines duked it out for years with no clear winner.

|

| Sinclair ZX Spectrum |

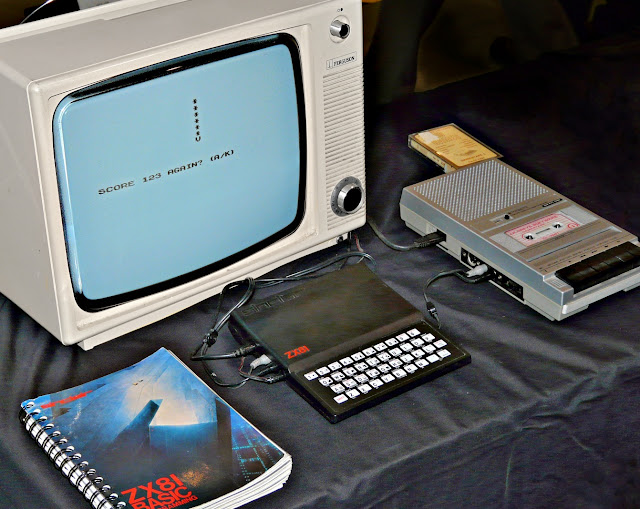

Out of the three, the cheapest and most popular (for a while) was the Sinclair ZX Spectrum. Sinclair’s follow-on to the ultra-low-cost ZX81 launched the year before, the Spectrum added rudimentary but usable colour, graphics and sound in a package with either 16kB or more desirably 48Kb of RAM in a stylish package – all at a very attractive price.

Like the ZX81, the Spectrum was based on a Z80 processor. But where the ZX81 struggled to do anything due to its clever-but-simple design, the Spectrum was highly competitive with the new generation of early 1980s home computers.

It wasn’t a big machine – roughly the size of a sheet of A5 paper and weighing around 550 grams – but Rick Dickinson’s industrial design consisting of a black case, grey keys and the 1980s-on-a-stick rainbow flash on the corner looked far more impressive than the competition. Those keys were something else though – each one performed up to six functions in the Spectrum’s capable BASIC environment, but the strange rubberiness of the keys felt like touching dead flesh.

The multifunction keys bear some examination. All the BASIC keywords were assigned to a key which would activate depending on context, or with the CAPS SHIFT and SYMBOL SHIFT keys. This layout was first seen on the ZX80 and while it reduced errors and made programming more accessible, it was becoming more fiddly as the version of BASIC evolved. The Spectrum’s version of BASIC was pretty sophisticated – not as good as the one in the BBC but better than the Commodore 64. Budding programmers took to the Spectrum and coded furiously from their bedrooms.

As standard the Spectrum loaded and save programs to a cassette, which was quite slow. Video output was to a domestic TV set, so the Spectrum could easily plug into what you probably already had in the house. The desirable 48Kb version cost just £175 at the time (equivalent to around £650 today) but you really didn’t need anything else if you had a TV and cassette recorder.

Like the BBC, the Spectrum could address only 64Kb of memory. The ROM was simpler than the BBC, taking up just 16Kb which left up to 48Kb of RAM available. The Spectrum’s curious colour graphics mode didn’t eat up much memory either, meaning that there was quite a decent amount of RAM available for programs, something that the BBC struggled with.

The colour graphics were rather strange. The 256 x 192 pixel resolution could display up to 15 colours, but you could only have one foreground (INK) and one background (PAPER) could in each 32x24 pixel character grid. This made it tricky to code colour games (for example) but it was very memory efficient. Sound output was fairly simple with a one channel output, but it was good enough for most purposes.

Like the ZX81 and ZX80, and edge connector on the back of the machine allowed access to pretty much all hardware functions. Sinclair’s official accessories on launch included a tiny thermal printer and the ZX Microdrive, which was a high-speed tape cartridge which was plagued with delays. Popular third-party addons included the Kempston Micro Electronics joystick interface but also various adapters for disk drives, speech, serial and parallel ports and perhaps most important a variety of aftermarket keyboards that improved on the Spectrum’s unpleasant chicklet affair.

|

| Spectrum with daisy-chained ZX Microdrives and sound enhancements |

The Spectrum was an enormous success - the combination of pricing, features and the brand recognition of the “Sinclair” name were key factors. Success bred success with huge variety of games and other applications along with hardware enhancements coming to market. Few competitors had a fraction of the third-party support that the Spectrum did.

1982 and 1983 were probably the peak years for the home computer market in the UK. Sinclair found itself up against increasing competition from less well-known machines which were often better (though rarely cheaper). In 1984 the Spectrum+ was launched, essentially a 48K Spectrum in a Sinclair QL-style case. A 128Kb version dubbed the Spectrum 128 was launched the year after, using memory paging to break the 64Kb limit. In 1986 Sinclair found itself in difficulties and was bought by Amstrad who styled new models after their popular CPC range leading to the Spectrum +2 with an integrated cassette recorder in 1986 and the Spectrum +3 which included a built-in 3” floppy disk drive, launched in 1987. This +3 was the ultimate development of the Spectrum platform, capable of running CP/M but it wasn’t 100% hardware compatible with the original which caused problems. The last Spectrum models in production were the +2B and +3B which were basically hardware fixes of previous versions, production ended in 1992 giving the Spectrum platform an impressive ten year lifespan.

|

| ZX Spectrum +3 with 128Kb RAM and a 3" floppy drive |

In addition to the official Sinclair version, licensed and unlicensed clones proliferated – notably licensed variants made Timex in the US and Europe, and a huge number of bootleg clones in Eastern Europe and South America into the 1990s. In the 2010s there were several attempts to recreate the Spectrum with modern technology, perhaps most significantly with the ZX Spectrum Next.

Despite the success of the Spectrum in the market, ultimately it was something of a dead end – even though fondness for the platform lingers on four decades later. However, the significance of the Spectrum was profound in the markets it succeeded in: this low-cost, easy-to-use and versatile device inspired a generation of programmers and computer enthusiasts, many of whom went on to carve careers out in the IT industry. This simple but effective machine not only help to shape lives, but also whole economies. Not bad for a cheap computer with a nasty rubber keyboard.

Image credits:

Bill Bertram via Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 2.5

ccwoodcock via Wikimedia Commons – CC BY 2.0

ccwoodcock via Wikimedia Commons – CC BY 2.0