Introduced February 1951

The years immediately after the end of the Second World War saw huge advances in the use of electronics and the development of early computers. By 1951, these machines were becoming practical – albeit in strictly limited scenarios – and February 1951 saw both the world’s first public demonstration of the LEO I and the delivery of the first Ferranti Mark 1 computers.

Both computer systems were British designed and built, they used vacuum tubes and masses of discrete components such as diodes and resistors, housed in huge boxes weighing several tons that sucked in electricity at a phenomenal rate. Primitive by today’s standards, the Ferranti Mark 1 and LEO I was early examples of successful commercial computers.

The computers had different markets, the Ferranti was aimed at scientists and engineers but the LEO was the world’s first dedicated business computer.

|

LEO Computer name plate

|

“LEO” stood for “

Lyons Electronic Office”, and it was a computer originally designed for the J Lyons company in the UK. Lyons at that time was a massive business of food manufacturing, tea shops and other hospitality businesses spread throughout the country. Almost every town had a

Lyons Tea Shop, making them the post-war equivalent of Costa Coffee or Starbuck today – and they had a huge number of customers and staff to support them, requiring a steady and uninterrupted supply of food to keep everything going.

It was a massive logistical enterprise, and Lyons managed it very successfully. Indeed, Lyons successful management of logistics led to the British government giving them the contract to run a large munitions factory called

ROF Elstow during World War II. Logistics was the key to the Lyons business, and this led to their interest in the developing world of computers.

The LEO I was designed to help with that. Inspired largely by the

EDSAC computer developed at the University of Cambridge, the LEO I started with the mundane task of bakery valuations before moving on to inventory management and payroll. Lyons even started doing payroll for other companies, and there was demand for LEO I systems from other large companies in the UK.

|

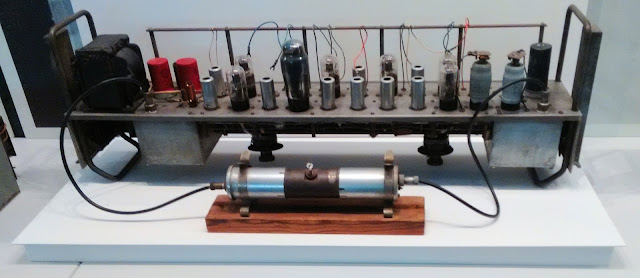

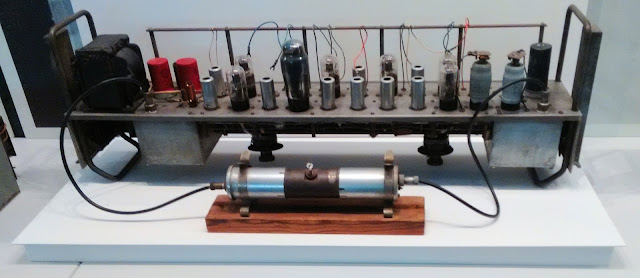

| LEO I Mercury Delay Line Storage Unit |

A few years later, the successful computer division was spun out as LEO Computers leading to the LEO II and LEO III which used more modern technology. In the 1960s, LEO Computers were merged into English Electric, then International Computers and Tabulators (ICT) and eventually found their way into ICL which itself was taken over by Fujitsu in 2002. The J Lyons company also faded away, by the 1960s the tea shops were losing money and despite a merger with Allied Breweries in the late 1970s, the profitable parts of the company were sold off but the Lyons name

lives on under different owners.

The

Ferranti Mark 1 had a different lineage – essentially a commercialised version of the

Manchester Mark 1 developed at the University of Manchester.

Ferranti themselves were a more traditional electrical engineering and electronics company, working in diverse markets such as defence, power systems and home appliances. Their experience in electronics in World War II made them an obvious choice to collaborate with the Manchester project.

Although both computers used vacuum tubes, they had very different forms of memory – the LEO used acoustic

mercury delay lines and the Ferranti used a CRT called a

Williams Tube. These technologies were only marginally viable even in 1951 and neither technology made it to the end of the decade. Data storage for both systems included the rather more long-lasting solutions of paper tape and punched cards.

Several generations of improved computers came after the Mark 1, but Ferranti wasn’t competitive in the business computer market so eventual sold that off to ICT (who became ICL), concentrating instead on industrial and military applications. Development of these computers continued into the 1980s, alongside Ferranti’s successful semiconductor business.

|

| Ferranti Mark 1 Logic Door |

But where J Lyons faded away, Ferranti’s end was more sudden and dramatic. A takeover of a US firm called

International Signal and Control (ISC) in 1987 was a disaster – although ISC looked like a good fit, it turned out that the books that Ferranti had inspected were false and instead of ISC being a profitable and above-board defence contractor, its real business was in illegal arms sales which were often made at the behest of the US government. These illegal contracts stopped as soon as ISC because British-owned leading to a massive black hole in Ferranti’s accounts. By 1993 it was all over, Ferranti collapsed and the viable business units were bought out by competitors.

It’s a familiar story of course, early innovators fall by the wayside and then disappear. Not every company can become an IBM or Apple, but in the case of Lyons and Ferranti rather more was lost along the way.

Image credits:

Ferranti Mark 1 Logic Door - Science Museum Group – CC BY 4.0

LEO Computer Name Plate - Science Museum Group – CC BY 4.0

LEO I Mercury Delay Line - Rhys Jones via Flickr – CC BY-NC 2.0