This year sees the anniversary of several well-known food brands, and a few lesser-known ones. It turns out that some have been around for longer than you might imagine… others, not so much.

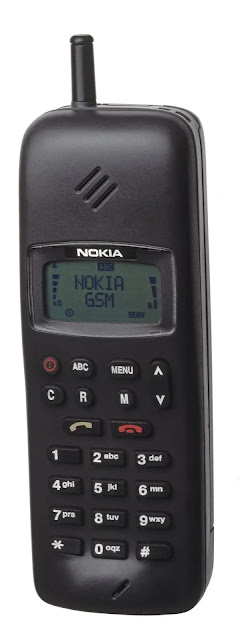

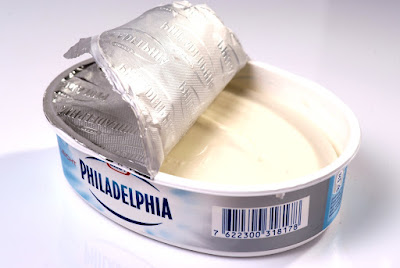

Philadelphia Cream Cheese started off life in 1872 in where else, but… errr… New York State. As sometimes happens, Philadelphia was an accident. In an attempt to make a crumbly French-style cheese known as Neufchâtel, too much cream was added which had the happy effect of making it easy to spread. Cream Cheese was born, and the Philadelphia brand became a success that is still widely enjoyed around the world today – although it has had many different owners during that time, today it is owned by Kraft.

|

| Philadelphia Cream Cheese |

A rather more polarising thing to spread on bread is Marmite. Introduced in 1902, this intensely savoury spread is made from yeast extract. More than something to put on your toast (or in a stew or casserole), Marmite also gives rise to a saying in British English that something is a “bit Marmite”, which means that people will either love it or hate it. The distinctive Marmite jars are shipped worldwide, and today the brand is owned by Unilever.

|

| Marmite and toast |

Yeast extract is a key ingredient in Twiglets, another British snack, introduced in 1932. Starting off life as a way to use up leftover dough, these unusual twig-shaped snacks are very savoury and are traditionally eaten at Christmas. Again, the brand has had a few owners and it is today a product of Jacobs, part of United Biscuits.

|

| Two bags of Twiglets |

The Mars Bar was invented in the same year – 1932 – by the British arm of Mars Incorporated. A worldwide success – with slightly different ingredients according to market – the British Mars Bar contains nougat and caramel coated in milk chocolate. The flavour of the bar is quite distinctive and has found its way into many authorised spin-off products. Somewhat less authorised in the artery-clogging deep-fried Mars Bar found in Scotland.

|

| Partially-eaten Mars Bar |

1932 was a good year for snacks. The Terry’s Chocolate Orange is another British product with strong sales around Christmas. Shaped like an orange, it consists of 20 segments of chocolate infused with orange oil, giving it a distinctive texture and taste. In order to separate the segments it needs to be hit on a hard surface first, giving way to the long-running advertising slogan “tap it and unwrap it”. Traditionally made from milk chocolate, other varieties are available plus a chocolate bar. The Terry’s company has had several different owners over the years, including Kraft, but is now owned by Carambar and made in France.

|

| Terry's Chocolate Orange |

Skip forward thirty years to 1962 and another iconic chocolate product was created by British firm Rowntree. After Eight mints are very thin chocolate mints, containing a fondant filling and traditionally served in a small box with each chocolate in an individual sleeve. Unlike many chocolate products marketed at young people, After Eights were marketed to adults as an upmarket product that could be eaten after dinner with coffee. Today the product is owned by Nestlé and made in Germany.

|

| Box of After Eight mints |

Switching back to cheese from chocolate and moving away from big corporations, we come to Stinking Bishop. This aromatic (some might say “smelly”) soft cheese was originally developed in 1972 by Charles Martell. Produced from the milk of rare Old Gloucester cows, the distinctive smell comes from the cheese being washed with a locally-produced perry (pear wine) made with the Stinking Bishop pear. The “stinking” part of the name came from the nickname of the ill-tempered farmer who grew them. The cheese itself would have remained obscure, but it ends up as a key plot device in the 2005 movie Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. As a product it remains stubbornly unavailable in supermarkets, but can be found at cheese specialists, delicatessens and some high-end retailers.

|

| Stinking Bishop cheese |

One thing that goes nicely with a nice piece of cheese is some nice bread. One of the best-known types of bread worldwide is ciabatta. You might think that this is a traditional Italian product, but in fact it was only developed in 1982. This white bread is notable for its inclusion of olive oil, giving it a unique texture and taste. The bread was developed in response to the success of the French baguette which was taking over the Italian market, and became a worldwide success in its own right… one that you wouldn’t think was just 40 years old.

|

| Slices of ciabatta |

Something that sounds Italian but isn’t, Viennetta is a brand of ice-cream also introduced in 1982. Consisting of layers of rippled ice-cream with very thin layers of chocolate in between, the Viennetta is a high-distinctive looking product. Despite the name, Viennetta was developed in the UK by Walls and the brand is now owned by Unilever.

|

| A very small Viennetta |

Another brand that isn’t as old as you might think is Diet Coke, introduced in 1982 and the perfect thing to wash down some high-calorie ice-cream. Although the Coca-Cola Company had made a sugar-free cola since 1963 under the “Tab” brand, they wanted to keep the “Coke” name associated with their flagship product only. However, the success of rival Diet Pepsi led to a change of plans and Diet Coke was born. Diet Coke has a slightly different taste from normal Coca-Cola, and in 2005 the company also introduced Coca-Cola Zero which has a taste closer to the original. Diet Coke (and similar products) are widely available, and are one of the few drinks you can reliably find if you want to avoid sugar.

|

| Quite a lot of Diet Coke |

Of course, other types of food are also available and you might want to balance out all the fat and processed ingredients with something healthy like a salad (invented some time in antiquity) and maybe a nice glass of water…

Image credits:

Philadelphia: POSt18 via Wikimedia Commons – CC0

Marmite: Rhino Neal via Flickr – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Twiglets: Adam Kuban via Flickr - CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Mars Bar: Asim18 via Wikimedia Commons – CC0

Terry’s Chocolate Orange: Brett Jordan via Flickr - CC BY 2.0

After Eight Mints: Like_the_Grand_Canyon via Flickr - CC BY-NC 2.0

Stinking Bishop: Stephen Boisvert via Flickr - CC BY 2.0

Ciabatta: tuhfe via Flickr - CC BY 2.0

Vienneta: cyclonebill via Flickr - CC BY-SA 2.0

Diet Coke: Niall Kennedy via Flickr - CC BY-NC 2.0