This year we’ve covered gadgets and inventions from the 1800s and up. But there are plenty of other things that had anniversaries this year that we didn’t mention.

One of the most important inventions debuted in 1810 – the tin can. A key product of the industrial revolution, the tin can answered many of the millennia-old questions about how to preserve foodstuffs. More reliable and palatable than salting, drying, pickling and a variety of other methods this humble tin can meant food security for growing populations in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries.

Also hailing from the nineteenth century was celluloid, a versatile class of materials that were pioneered in billiard balls in 1870, and then found their way into many other products from toys to films. However, celluloid’s habit of bursting into flames means that it is rarely used as a material today.

|

| Canned food in a store in Hong Kong, Easter brooch with celluloid flowers |

Somewhat related to celluloid is cellophane, a lightweight and flexible material that lent its properties to Scotch Tape, introduced in 1930. Also from 1930 – and perhaps a little bit more edible – is the Hostess Twinkie cake bar. Allegedly, Twinkies last forever – but eat a decade-old box at your own risk.

|

| Vintage scotch tape container, Twinkie cake bars |

Fast forward to 1960 and the white heat of technology forges something even more high-tech than sticky tape and cake bars, with the laser. Don’t ask me to explain how these things work, they just do. Pew pew.

|

| Visible lasers being demonstrated |

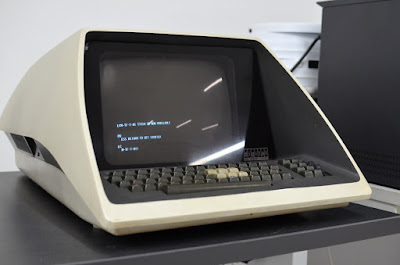

People who remember the home computers of the 1980s probably remember the Commodore VIC-20 – but it had an immediate predecessor in the shape of the VIC-1001 which was sold successfully in Japan only. The main difference between the two is that the VIC-1001 supports Japanese Katakana characters.

|

| Commodore VIC-1001 |

By 1990 of course things were really getting more advanced. The Sega Game Gear was an 8-bit handheld console that carved a significant market for itself. Another 8-bit games machine, the Commodore 64 Games System (or simply the C64GS) was a more traditional console based closely on the legendary Commodore 64 home computer. The C64GS held great promise with the potential of a huge games library, but it failed to deliver in a spectacular way.

|

| Sega Game Gear, Commodore 64 Games System |

In the same year, the Macintosh Classic breathed a bit more life into a familiar format at a sub-$1000 price point, but the 68000 processor was getting a bit long in the tooth by then. More powerful, but three times the cost, was the 68030-based Macintosh IIsi which was much more forward-looking.

|

| Apple Macintosh Classic, Macintosh IIsi |

Handheld gadgets continued to develop, and in 2000 the Sharp J-SH04 was launched in Japan which was the world’s first recognisable camera phone, with a rear-facing 0.11 megapixel camera. It wasn’t great, but it set a pattern that other early camera phones improved on.

|

| Sharp J-SH04 |

That’s it for 2020, a difficult year for many people. Let’s hope that 2021 will be better. A big shout out to all those key workers, healthcare professionals and everybody trying to be socially responsible (or even just managing to keep themselves sane) this year.

Image credits:

Canned food in a store in Hong Kong: Bairgae Daishou 33826 via Wikimedia Commons - CC BY-SA 4.0

Easter brooch with celluloid flowers: Pinke via Flickr – CC BY-NC 2.0

Vintage scotch tape container: Improbcat via Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 3.0

Twinkie cake bars: Photog Bill via Flickr - CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Visible lasers being demonstrated: US Navy via Wikimedia Commons – Public domain

Commodore VIC-1001: Thomas Conté via Flickr - CC BY-SA 2.0

Sega Game Gear: James Case via Flickr - CC BY 2.0

Commodore 64 Games System: Thomas Conté via Wikimedia Commons - CC BY-SA 2.0

Macintosh Classic: Christian Brockmann via Wikimedia Commons – CC0

Macintosh IIsi: Benoît Prieur via Wikimedia Commons - CC BY-SA 4.0

Sharp J-SH04: Morio via Wikimedia Commons - CC BY-SA 3.0