Introduced December 1981

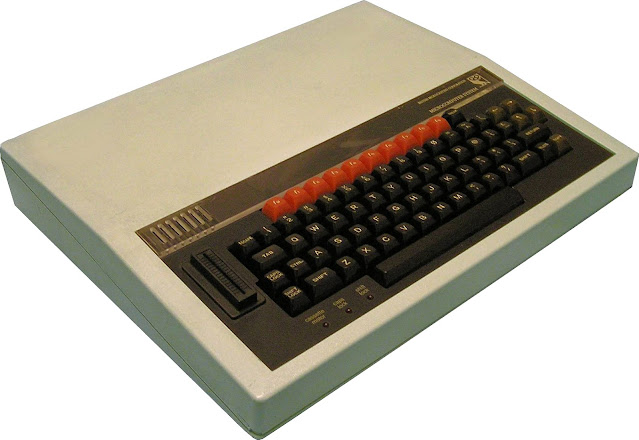

If you were to make a shortlist of microcomputers that epitomised the very peak of 8-bit technology, then the BBC Micro would probably be part of that list, especially if you were British. Pushing the limits of what was possible, the BBC Microcomputer (often just referred to as the “Beeb”) introduced several features that were considerably more advanced than rivals and produced a series of machine that were available – in one form of another – for 13 years, leaving behind a lasting and arguably world-changing legacy.

|

| BBC Microcomputer |

The story starts in the late 1970s in the wake of the launch of the Apple II, TRS-80 and Commodore PET – three computers that made computing relatively affordable and simple, and which challenged traditional large-scale computers used in big businesses. It wasn’t just on the desktop either, microprocessors were finding their way into everything and it seemed very likely that the 1980s was going to be a digital age – one that both the British government and the BBC thought the country was ill-prepared for.

The BBC set out to educate the masses, in line with its public service charter. This idea became the BBC’s Computer Literacy Project, and at the heart of the project was an idea to teach people how to use a computer – which for practical purposes would concentrate on a single model of machine.

But which to choose? It needed to be a British company ideally, and there were several to choose from. Promising systems had been developed by Tangerine, Research Machines, Sinclair, Acorn, Nascom and Transam… but the BBC chose Newbury Laboratories and their still-under-development microcomputer which later became the Grundy NewBrain.

The NewBrain itself has an interesting history, but it didn’t become the BBC Micro. Production problems meant that the computer wasn’t going to be ready for sale in the BBC’s timescale so instead they approached Acorn who had achieved some success with their 6502-based Atom machine. Acorn were already working on a replacement for the Atom, called the Proton.

Despite being only a few years old, Acorn had quite a lot of development under its belt. In addition to the Atom, they had a range of Eurocard systems that offered expandability and reliability, but at a price. The Proton would be an expandable and fast system, but when the BBC approached Acorn it was only a paper design but a frantic effort managed to create a prototype which was stable enough to show the BBC… who were impressed. Acorn were offered the contract, subject to some design changes.

The Proton pushed the 6502 processor to 2MHz, twice that of the competition. Paired with fast memory sourced from Hitachi and some clever circuitry to make everything work at these breakneck speeds, the Proton was no slouch. Internal memory was a maximum of 64 kilobytes, 16Kb of ROM was the operating system, another 16Kb of ROM was BASIC or any other application that could be loaded from the four ROM sockets on the board, leaving 32Kb of RAM (on the Model B) which was shared between the computer’s workspace, graphics and the rest could be used for programs and data.

There wasn’t a lot of RAM in the machine as the 6502 could only address 64Kb of total memory, and half of that was the system’s ROMs on this machine. Futhermore high-resolution graphics could take up 20Kb of the 32Kb of RAM, and with about 6Kb of RAM as the computer’s own working area this could mean that less than 6Kb was available for the user. This wasn’t a lot and it would have badly impacted the usefulness of the machine. Worse still, 32Kb of RAM was a feature of the more expensive Model B where the cheaper Model A had just 16Kb which was not even enough to display high-resolution graphics.

However, the BBC insisted that any machine they were to commission needed to be able to display Teletext, and Acorn had already implemented this in some of its machines using a Mullard SAA5050 chip. This gave 40 column text and rudimentary block graphics while taking up just 1Kb of the precious RAM. Known as display “Mode 7”, this feature became a key part of the BBC Micro’s success.

Then there was expansion. The Model B had lots of ports – on the back were three types of video output, a serial port, cassette interface plus an analogue-to-digital port plus an optional Econet network interface. Underneath were more ports that used a ribbon cable connection – a parallel port, a connector for the optional floppy disk drive plus a power output and then a user port, 1MHz bus port and a clever interface called the Tube. Apart from the floppy disk and network ports, everything was included in the BBC Model B as standard.

The Model A was based on the same board as the Model B, but lacked a lot of the interfaces. It was possible to add them in though, but this required some work with a pile of components and a soldering iron. Upgrading either model to a floppy disk drive or Econet required opening up the machine and plugging in some new components too.

With all of these interfaces you could hook the BBC up to just about anything, assuming you had the right cables, including lab equipment, joysticks, mice, modems, printers, Teletext and Viewdata adapters and more. You could do that with other computers too, but the Tube interface was something different again.

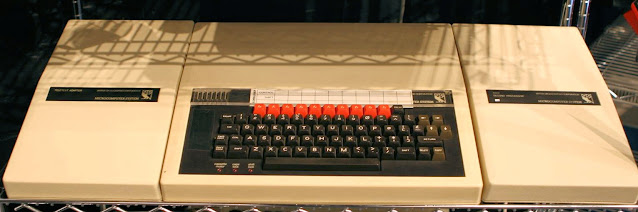

Acorn built the system to be expandable, and the Tube was a way of connecting a second processor to the BBC. This wasn’t a coprocessor, these units essentially took over and reduced the BBC Micro itself to handling input and output only. These processors could be anything at all – Acorn (eventually) provided a 6502 or Z80 (both with 64Kb of their own RAM) and a National Semiconductor 32016 with up to 1MB of RAM. Other companies produced other second processors too, including the Motorola 68000 or Intel 8088. Because the work was now split between two computers, these solutions could be both fast and made lots of RAM available. Although none of these add-ons were very common, they did offer a lot of power for the price.

|

| BBC Micro with Teletext Adapter and Second Processor |

Mostly though, BBC setups were more modest. Typically paired with one or two 5.25” floppy disks (which could cost as much as the computer), a printer and a TV (or if you were lucky a Microvitec Cub monitor). They were versatile machines for small businesses, were pretty good for games (although the lack of RAM was always a problem) but most of all they succeeded in education where their robust design and wide variety of software made them the most common computer in schools at the time.

The built-in BASIC was also very fast and allowed structured programming, becoming a popular platform for bedroom coders who would then take their skills out into the real world when they started careers in IT.

Games were always a bit of a problem – compared to the rival Sinclair Spectrum and Commodore 64, the lack of RAM meant porting popular games from those platforms difficult or impossible. But in 1984, Acornsoft announced Elite - – space trading gaming the capitalised on the strengths of the BBC. In Elite, the player flies a spaceship flying through an impressively rendered 3D space environment with wire frame graphics with hidden line removal. The galaxy the player is in is procedurally generated, a semi-random technique that allows for a great variety of locations but with little memory used. Elite had a clever trick of managing to display two screen modes at the same time – something regarded as impossible – giving high-resolution black and white 3D at the top and a more colourful status bar at the bottom.

Upgraded versions of the BBC followed, the Model B+64 and B+128 adding more RAM through paged memory, and the more substantially upgraded BBC Master which took the computer into the 1990s. A cheaper version of the BBC called the Acorn Electron met with limited success. But Acorn had something else up their sleeve which was ultimately more important – the Acorn Archimedes, the world’s first production computer with an ARM processor. The ARM itself was designed by Acorn and was largely shaped by their experience with the simple, speedy 6502 found in the BBC.

|

| Acorn Electron |

Because it was both a popular machine and very reliable, there are lots of BBC Micros on the market today. Typically the capacitors in the power supply fail over time and need replacing, but other than that there are few problems. Floppy disk drives are another matter though, these can be quite rare. A complete working system with accessories can be worth well over £500.

You can argue at length what the ultimate 8-bit computer was, but the unique expandability options of the BBC surely make it a contender in any contest. The ARM processor which it inspired is – of course – what the world runs on today,

Image credits:

StuartBrady via Wikimedia Commons - CC0

marcus_jb1973 via Flickr - CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Steve Elliott via Flickr - CC BY-SA 2.0

Adam Jenkins via Flickr - CC BY 2.0