Introduced August 1981

Four years on from the launch of the holy trinity of the Apple II, Tandy TRS-80 and Commodore PET there was a rapidly growing (but fragmented) multi-million dollar market worldwide. Although rival micros tended to be incompatible, business systems showed a growing standardisation around the CP/M operating system and the S-100 expansion bus. Home machines had wildly different hardware and software, but tended to be based around either the MOS 6502 or Zilog Z80 CPUs.

|

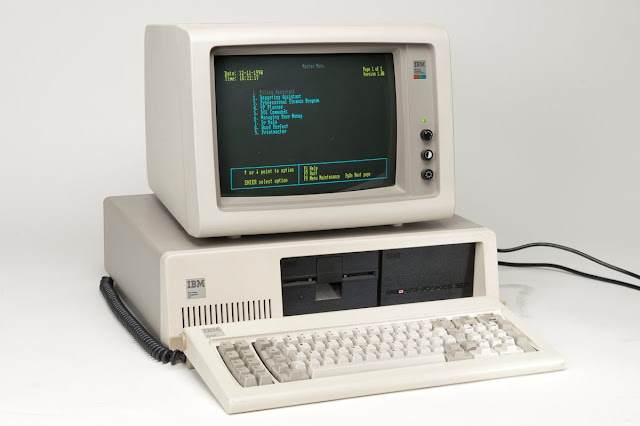

IBM Model 5150 and 5152 printer

|

But in August 1981 came a paradigm shift, thanks to IBM. IBM seemed an unlikely player in the microcomputer market, specialising in powerful but incredibly expensive mainframes and whose initial microcomputer systems were also blistering pricey. It took IBM at least five years to develop a product, which was much slower than the microcomputer market was moving. IBM seemed old-fashioned in a market that was mostly dominated by younger and more agile competitors.

IBM could sense the way the wind was blowing, however. Cheap but versatile micros were finding their way into IBM customer sites while at the same time the market for big iron computing was faltering. IBM wanted a slice of the micro market, while at the same time it was aware that its traditional business processes would not be able to compete.

In a moment of enlightenment, IBM took one look at its internal rulebook and tore it up. Their entrance into microcomputers would follow a completely different path. Dubbed “

Project Chess” by IBM, the development work attracts many top-flight IBM engineers to work on this new computer in complete secrecy. The result was the

IBM Model 5150 - best known as the IBM Personal Computer or simply the IBM PC.

Instead of basing the PC around an IBM CPU, an

Intel 8088 was chosen – as seen in the

IBM Datamaster which was being developed at the same time. The PC also took a variant of the Datamaster’s keyboard and expansion slots, but then developed features all of its own. Output was either crisp text via a Monochrome Display Adapter (MDA) card to an existing model of IBM monitor, or to an compatible colour monitor with a Colour Graphics Adapter (CGA) card.

Although the PC could run a version of CP/M, the primary operating system was PC-DOS which was sourced from Microsoft. Quite how this choice of OS was made is now the

stuff of legends. Initially IBM approached Digital Research (DR), the makers of CP/M, to provide a software platform for the PC. Although CP/M was designed to run on the Z80, an Intel version had been developed as well. Legend says that the boss of DR – Gary Kildall – was out flying his private plane when IBM turned up at the office unannounced, although the truth probably that DR and IBM couldn’t agree on a licensing structure. IBM then approached Microsoft and asked them to provide an OS. Microsoft didn’t actually make operating systems – their main business was BASIC – but a nearby company called

Seattle Computer Products had an OS called QDOS that would run on the 8088. Microsoft bought the rights to QDOS, renamed it MS-DOS and then licensed it to IBM as PC-DOS while retaining the rights to sell MS-DOS themselves.

|

| IBM PC with neatly-labelled floppies |

Compared to PCs of even just a few years later, the model 5150 was pretty limited. The 8088 was a cheaper and more readily available version of the 16-bit 8086, but the 8088 only had an 8-bit external bus. RAM was theoretically expandable to 640Kb which was substantially more than the competition, but typical configurations topped out 256Kb. Although the 5150 supported twin floppies (up to 320Kb each) the only way to support a hard disk was to use the

5161 expansion box which wasn’t available at time of launch.

The 5150 did have a cassette interface, although almost all systems were bought with floppy drives. Typical configurations would include two serial ports and a parallel port, but eventually you could add a joystick, network card, more memory and other options. The 8-bit expansion card design was physically robust, and IBM published all the specification so that third-party vendors could make their own.

IBM had a rebadged

Epson MX-80 printer available as the IBM model 5152, the most popular dot-matrix printer of the time. You could add any other parallel or serial-port printer as long as your software had the drivers for it.

The use of an open architecture (where IBM described in detail the workings of the machine) plus industry standard components made this a very flexible system. Because it was well-built and designed – albeit expensive – it became a popular business computer, although realistically it was priced too high for the home market. Third-party software and hardware followed, so within a year of launch the PC could do everything any other machine could do plus much more.

It was a huge sales success, outstripping IBM’s most optimistic projections several times over. High demand meant that most initial units were sold in the US only. Production of machines for Europe officially started in 1981 when IBM launched a plant in Scotland, but grey imports existed before that. This delay gave the opportunity for rivals such as the

ACT Sirius 1 to gain a foothold.

The 5150 was the direct ancestor of almost all PCs in use today (apart from Apple’s Macintosh machines). The

IBM PC XT added more expansion slots and hard disk support in 1983, the

IBM PC AT came in 1984 and used a much more powerful Intel 80286 CPU. It did seem at the time that IBM was onto a winner, but it didn’t take long for other companies to build compatible machines using the same architecture.

The only proprietary part of the PC was the BIOS which had to be emulated, or in some cases just ripped off from IBM. The

Columbia Data Products MPC 1600 was the first true clone of the PC, launched less than a year after the 5150. Better known was the

Compaq Portable, launched in 1983, which was not only 100% compatible (and used a legal BIOS) but it was transportable too. Thousands of other companies followed suit, and within a few years IBM’s control of the market was slipping.

In 1987, IBM attempted to change the direction of the PC industry with the launch of the

PS/2 range which was more tightly controlled by IBM. Clone makers needed a licence to make a PS/2-type machine which had a different hardware architecture, but few bothered and instead the bulk of the market remained with machines with a direct line back to the original 5150. IBM continued in the PC business until 2005 when it sold the unit to Lenovo.

Today the 5150 commands decent prices for collectors, commanding prices of several hundred pounds for a good one, although they are much rarer in Europe than the United States (and if importing one, you need to get a voltage regulator unless you want to blow up your power supply). Of course, you can buy a direct descendant of the original PC in any computer shop which might give you a less antique experience…

Image credits:

Science Museum Group - CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Rama & Musée Bolo - CC BY-SA 2.0 FR